When Janet first invited me to speak about the idea of writing spiritual stories my mind raced off in all directions. What would you want to know? The truth, my truth, my spiritual path… or your own? Because as writers, that’s part of what we do isn’t it? We not only create stories but in the making of them, we tell the story of being alive, along with the merging of fact and fiction we bring something unique, something of our inner lives along the way.

Helen Dunmore, who managed to successfully write for both adults and children, published a trilogy for her younger audience. She wrote about the undersea world of mermaids and what prompted her, she says, was sitting on a beach, looking out at the sea and wondering…

‘what if you could just slip through the skin of the water, what would you find?’

And it’s that eternal question, ‘what lies beneath the surface’ that forms part of the fascination for me as a writer.

As children it’s said we occupy an in between state… that for a time we have one foot here in this world, while another appears to be someplace else. I still remember some of my own entry points between worlds, when a space opened up, quite literally, in a

fence. I was eleven when we came to live by a beautiful park. We had just spent a miserable time without a proper home to live in and when the offer of a prefab came up my mum took it. The house was tucked away in a relatively quiet corner of South East London.

One summer evening, soon after we moved in, my sister and I went along to the park and finding the gates locked we looked for another way in. Soon we found a gap in the railings and I can safely say we frolicked. To have all that space to ourselves after being cooped up in temporary housing, with no garden or anywhere to play, felt like heaven. I particularly remember rolling down a bank of grass and coming to rest at the bottom I lay there and let myself drink it in. It was at this moment I had the most wonderful feeling of connection. It was as if my ordinary self had suddenly grown huge. In fact it felt as if I was outside of my body, with the sky above me no longer millions of light years away – it was here, right now and I was very much part of it.

As children I think our concepts of what’s real are far more open .to possibilities. May I read you an extract from an old children’s book? ·

The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams

“What is REAL?” asked the Rabbit one day, when they were lying side by side near the nursery fender, before Nana came to tidy the room. ‘Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?”

“Real isn’t how you are made, “said the Skin Horse. “It’s a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real. “

“Does it hurt?” asked the Rabbit.

“Sometimes, ” said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. “When you are Real you don’t mind being hurt. “

“Does it happen all at once, like being wound up,” he asked, “or bit by bit?”

“It doesn’t happen all at once,” said the Skin Horse. “You become. It takes a long time. That’s why it doesn’t often happen to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept. Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in the joints and very shabby. But these things don’t matter at all, because once you are Real you can’t be ugly, except to people who don’t understand”.

Clearly the author meant for the story to be read on different levels. It not only speaks to the adult reading the story at bedtime but also to the subconscious mind of the child – and there are different approaches we can use, whatever the age of our audience.

David Lodge says something interesting about this.

Consciousness and the Novel

‘In a world where nothing is certain, in which transcendental belief has been undermined by scientific materialism, and even the objectivity of science is qualified by relativity and uncertainty, the single human voice, telling its own story, can seem

the only authentic way of rendering consciousness.’

As writers we go about our rendering artfully, creating an illusion of reality that is mindful, that uses a wealth of different devices… the personal witness, the diary, the confession, the memoir. A couple of summers ago I entered a short story for the London Writers Competition, in which my narrator observes the scenes unfolding from a very different viewpoint.

Rhubarb and Coco

I watch as Mum moves through the shed, speaking low and gently rubbing the tips of their velvety leaves. ‘You ‘re in the best place, ‘she tells them. I’m invisible to her but I wonder if she can still sense me, gliding with her as she walks through the moist wood

of the shed. She carries with her a hurricane lamp filled with gas, because she knows that even at night the rhubarb never sleep.

Inside here they grow better than anywhere else on the farm. With no slugs to bother them the rhubarb lay tucked up warm and safe in their beds. Mum makes sure that the humidity is just right, the long white candles dotted amongst them gently warming

their roots. It’s really two sheds joined together, an idea that came later after Mum realised she needed more space. She bends her head and passes through the doorway cut into one of the walls, continuing along her path and I follow her. As she stops and

pays particular attention to one of the plants I can tell by the shine in her eyes that something is about to happen. I look at the same spot in between the overarching leaves.

Then I’m there, diving into the soil, down, down I go, until I can see the rhubarb’s roots right in front of me. They wriggle like worms in a mouldy fruitcake and I watch as the dark brown earth separates. Like time-lapse photography I’m seeing them

close up and moving at their own pace. I’m no longer frightened by this power that I have. This is one of those times I love being able to explore the earth without a body. The first time I pushed my face into the soil it was like being doused in cold water, it

was such a shock. Gradually I woke up to being dead’.

But I don’t believe your narrator has to be dead in order to give an account of the ineffable. More recently I wrote a short story for adults about a woman who forms an unusual obsession with a tree outside her bedroom window. There were various strands that led me to write it but it was based on a poem I’d written some time before, following a walk one day in a wood.

The Pagan Tree

A tree that curls up to the sky, lets out a sigh as you trail by. Bodies writhe, heads and feet, offshoots of family that meet.

Deep in the curvature of its spine, lies a secret that is divine.

Arms outstretched, its bark is bleached, anointed by the rosehips, as they sleep.

The time will come for you to mingle into the Pagan Tree, shackles shaken, hearts awakened, releasing you and me.

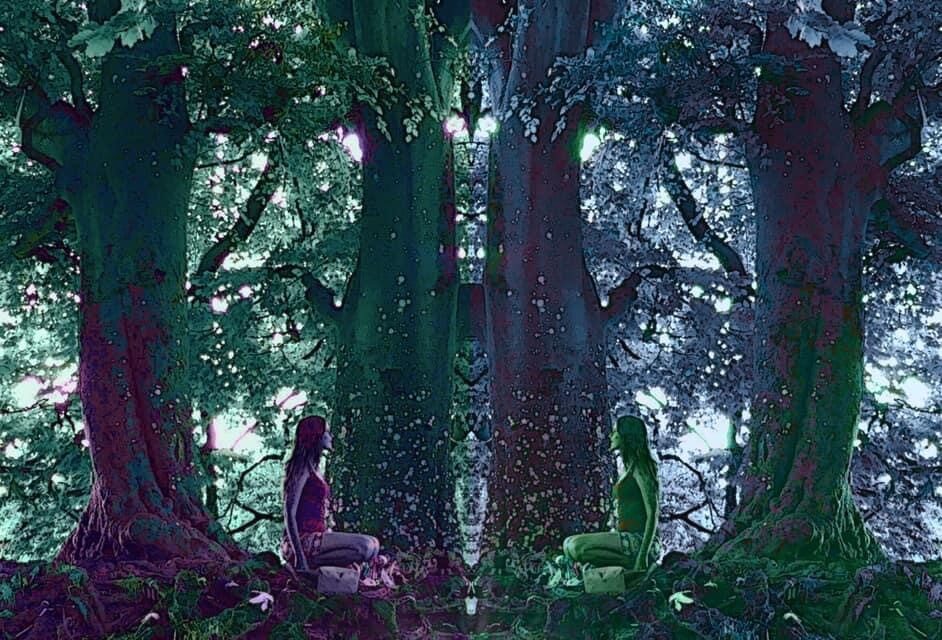

I came across this sensuous image, a photograph by Annie Brigman, around the time I was writing the story – so it’s not just my mind that conjures up these images. But I think any identification we have with an immortal soul or an immaterial self, is always going

to be weighted towards a greater mystery.

Thinking back to David Lodge again, he observes how as writers we vicariously try to possess this continuum of experience, in a way we’re never able to in reality. We are forever conscious of our existence in time, moving from a past that we recall very patchily into a future that’s unknown and unknowable.

So our journeys need to have recognisable features, landmarks. I wrote part of a historical fantasy for children, to form part of my dissertation. I used a time-slip device to explore the past’s effect upon the present.

Like children, I believe we have a need to know where we’ve come from in order to be able to move forward. Interestingly, I returned to my own ‘slice of heaven’ in my story – the park which I mentioned earlier. I took some inspiration from the French philosopher, Gaston Bachelard, when he talked about the notion of an ‘oneiric house’… a house of the imagination, built upon our own ‘dream memory.’ The protagonist of my story discovers a time-slip in the park which enables her to visit a palace, made of glass. E. Nesbit, the forerunner of the time-slip story also loved to include palaces in her stories but mine was the embodiment of shimmering dreams, wonders and treasures, stored for a nation. It was based upon the real life Crystal Palace exhibition, once sited in the park I played in.

At the heart of the palace, Remy, my protagonist, discovers her father’s ‘chrysalis’ and in the words of Gaston Bachelard ‘an immense synthesis’ begins to take place.

The Glass is Melting

He looked just like Dad or her dream of him. She tried to make sense of all the pieces, even though her mind had splintered as she stood surrounded by glass. Had she become caught in the wrong time? Had the Sultan called her back, even though there had been no warning? Outside, the glass everything was milky white, like the dream of the hospital. What was Dad doing here? Was this just another dream? She remembered standing beside him at the bed.

‘Dad. It’s Remy. Can you hear me? ‘

He seemed locked away, just like all the other times. But she was wrong.

Slowly his head turned towards her and blinked. It was like watching a ventriloquist’s wooden dummy come to life.

‘Remy, is that you?’

‘Yes Dad! It’s me’

His eyes filled with tears.

There was Just enough room for him to hold out his arms and Remy took a step forward, sure that at any moment the dream would end. But it felt so real. She could even hear his heart beating in time with the rhythm of the metronomes. It was then that she realised that the glass was moving.

‘Dad, look what’s happening.’

Remy held out her fingers to touch the front of the cabinet. ‘The glass is melting.’

And he did the same, holding out a hand.

‘Remy, you’re right,’ he said. ‘It’s going.’

The glass was slipping and sliding, trickling down into a river of liquid before turning into a pool of sand. Time was running out just like an hourglass and Remy could distinctly hear the sound of ticking. Could it be the metronomes?’ The glass had gone and taken her Dad with it until Remy now stood alone on the stage. There was no longer a white mist outside the cabinet, instead Remy could see the audience were leaving, hurrying quickly towards the exit.

But Albi was watching her. He looked astonished, his mouth hung open, gaping like a fish.

‘Who are you?’ He said.

‘Please sir, you must leave at once. ‘A palace attendant tried to call his attention, keen that the magician should join his fleeing audience. But Albi continued to stare at Remy. He was not accustomed to seeing a real live spook, let alone a time-traveller. Remy made a dash for the purple curtains, the same ones she had hidden behind with Cai on the first night. She knew that somewhere behind them lay a door.

Albi ignored the pleading attendant, shaking him off and raising his arm to point at her.

‘You! Come back here at once!’ He bellowed.

But Remy had no intention of staying to listen. She knew now was the time to run.

Phillip Pullman, says that ‘fiction has unlimited potential to explore all sorts of metaphysical and moral questions’ and for my part, I’m sure my own exploration, certainly in fiction·, has only just begun.

Photo credit and appreciation goes to Infinity Artworks.